In November 2021, the 197 parties to the Paris Agreement met in Glasgow at the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). COP26 culminated with the parties reaffirming the goals of the Paris Agreement, in particular resolving to pursue efforts to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, in the Glasgow Climate Pact.1

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) in three tranches between August 2021 and April 2022, covering the physical science behind climate change and its impacts, the vulnerabilities of the global system to climate change and the required adaptations, and the actions needed to mitigate its worst impacts, including limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C2 – an increase which the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) has predicted has a 66% chance of occurring in the next five years.3 Floods (such as that of the Rhine in February 2021), freezes (such as the Texas winter freeze in February 2021) and fires (such as those in British Colombia between June-October 2021) have caused disruption to supply chains,4 and analysis has found that increased damages climate-related physical risks have led to increased exposure for insurers.5 A 2022 survey of senior executives in companies and funds in Africa and Asia found that 68% of respondents said that climate change is affecting their business today.6

As the effects of climate change and the actions needed to address them increasingly materialise, the links between climate change and financial risk are becoming increasingly evident and inextricable. Our understanding of climate change has evolved from a purely “ethical issue” or “environmental externality” to an issue that poses foreseeable financial risks and opportunities for companies across short, medium and long-term horizons.

Indeed, the World Economic Forum’s 2023 report on global risks ranks failure to mitigate and failure to adapt to climate change – along with impacts which may become more likely as a result of climate change, such as large-scale involuntary migration, and large-scale environmental damage incidents – within the top 10 risks by severity over the next two years.7 Over the next 10 years, failure to mitigate and failure to adapt to climate change are ranked as the most severe risks.

The scale and speed of climate change risks and opportunities in the transition to a zero-carbon economy received heightened attention in May 2021 with the release of the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s first-ever attempt to model a feasible pathway to net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 (NZE2050), and the implications of the NZE2050 scenario for companies in the industry sectors facing either accelerated decline or rapid growth are momentous. The NZE2050 scenario has formed the basis for a number of shareholder resolutions, court cases, and engagements with government bodies.

However, the UNFCCC has found that the international community is falling far short of the action required, with predicted temperature rise caused by countries’ existing policies predicted to be 2.8°C; and the credibility of even these existing policies is uncertain. Indeed, “wide-ranging, large-scale, rapid and systemic transformation is now essential to achieve the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement”.8

Companies operating in industries facing structural decline can expect heightened pressure from investors to stress-test their businesses against these new data, and to demonstrate their ability to remain resilient in the face of uncertainty regarding the pace of change, failing which access to capital will continue to suffer headwinds. For directors, this adds yet another factor they must consider in the boardroom when modelling risk and strategic options.

According to the 2017 recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), climate change is one of the most significant and complex risks facing organisations.9 The TCFD recommendations have attracted the support of over 3,800 organisations, which demonstrates reflects the growing consensus among the business, financial and regulatory communities of the financial and systemic risks presented by climate change and of the necessity of embedding climate change in financial risk management, disclosure and supervisory practices.10

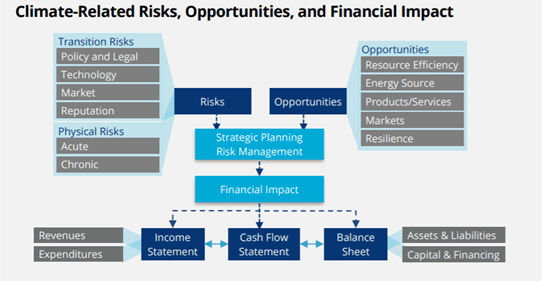

Figure 1: Climate-related financial risks to entities.

(Source: TCFD Final Recommendations (2017) p. 8)

In 2018, the Bank of England Prudential Regulation Authority explained that these financial risks have distinctive elements. The risks are far-reaching in breadth and magnitude across the economy, involve uncertain and extended time horizons, are foreseeable, and – crucially – the magnitude of future financial risks depends in large part on decisions taken today.11

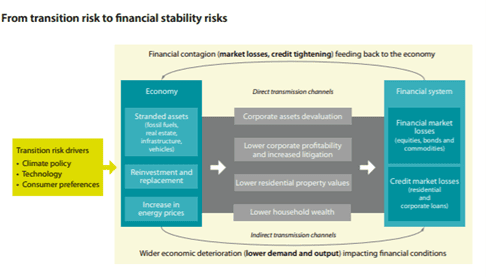

Moving beyond company-specific financial risks, climate change is now recognised as a systemic risk. This was made clear in 2019 by The Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a global coalition of over 110 central banks and supervisors, in its first comprehensive report, A Call to Action, which stated:

Climate-related risks are a source of financial risk. It is therefore within the mandates of central banks and supervisors to ensure the financial system is resilient to these risks.12

According to the Banque de France and the Bank for International Settlements, known as the 'central bank of central banks', the radical uncertainty of climate change and society's responses to it mean that climate change poses 'green swan' systemic risks that could lead to a financial crisis.13 Stress tests which cover climate-related risks are planned or have already been conducted by central banks around the world, including the European Central Bank, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Bank of England, which published the findings of its Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario in May 2022.14

Figure 2: Climate-related systemic risks arising from transition risks.

(Source: NGFS Guide for Supervisors: Integrating climate-related and environmental risks into prudential supervision (2020) p. 13)

As a now widely-recognised financial and systemic risk, as well as a factor that is integral to value creation, climate change squarely engages directors’ duties and disclosure obligations. In line with these developments, financial regulators have increasingly insisted on effective climate risk disclosure and governance.15

So, too, investors have set normative expectations of director conduct.16 A new coalition of financial institutions with over launched at COP26, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), has published guidance for its members on expectations for real-economy transition plans, portfolio alignment with achieving a net-zero by 2050 goal, and managing a phaseout of high-emission assets.17 The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), a membership body with over €51tn asset under management (AUM), has published policies and guidance for members on engaging with investee companies on climate matters;18 and the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, a group of asset managers with more than US$61.3tn AUM has published its initial targets for managing its assets in line with achieving net-zero by 2050 or sooner.19

Investors are also becoming increasingly vocal in communicating these expectations in their voting and stewardship activities. In 2021, shareholders at large oil and gas companies brought resolutions requesting that these companies set and report on climate targets,20 and, notably, investors voted to replace three of ExxonMobil’s board members with alternative candidates with experience in the transition of oil and gas companies.21 2021 was not an exceptional year. In 2022, over 215 resolutions relating to climate change were been filed by shareholders.22

Investors, regulators and governments are also increasingly asking companies to produce net-zero transition plans, setting out items including the company’s ambition, the activities covered by the plan, targets and dates, proposed use of offsets, financial impacts, and plans to engage through their value chain.23 First-mover companies have already begun to produce climate transition plans, and investor groups including GFANZ have published guidance on what they expect investee companies to include in their business plans.24 The U.K. government has stated that it will introduce regulations to require asset managers, regulated asset owners and listed companies to publish net-zero transition plans on a ‘comply or explain’ basis from 2023, and has established the Transition Plan Taskforce (TPT) to develop guidance and standards for these plans, which it has produced.25 In the EU, the proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) would require companies to adopt a plan to ensure that the business model and strategy of the company are compatible with the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.26

Investors are also encouraging companies to increase the ambition of their net-zero targets, which moving towards increased standardisation between targets. Race to Zero, an a global campaign with support from businesses, cities, regions, investors, has published criteria for its members, which include a net-zero pledge, covering scope 1, 2 and material scope 3 emissions, made from the top level of the company.27

Sustainability standards requiring disclosure of metrics and targets are steadily converging towards similar requirements. In June 2023, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) published its finalised sustainability reporting standards, which are aimed to bring about a harmonised framework for sustainability disclosures, including those relating to climate. The ISSB climate standard (IFRS S2), if adopted by domestic law, will require companies to disclose physical and transition climate risks facing their business model, their scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, their resilience to climate impacts using different scenarios, and information about their transition plans.28