What do directors’ legal duties require or permit?

By Charlene Cranny, Senior Manager for the CGI Financial Sector Programme and Sarah Hill-Smith, Climate Lawyer at the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative.

This guide is the first in a three-part series capturing insights from a workshop delivered by our Financial Sector team at Chapter Zero France's NED Program, held alongside ChangeNOW in Paris.

The session explored policy disruption and the increasingly polarised public discourse around ESG, climate, and sustainability.

In this part, we focus on legal duties: a concise but powerful exploration of how managing climate and nature risk intersect with directors’ legal obligations, as presented by Sarah Hill-Smith, climate lawyer at the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI).

Legal opinion is clear

Directors must actively manage material climate and nature-related risks. This exists separate to regulatory compliance and ‘anti-ESG’ policy.

Lawyers around the world have confirmed a simple truth: climate and nature-related risks are material financial risks to businesses that directors must actively manage to comply with their legal duties. Failing to do so exposes directors to legal liability for breach of duty, as well as the financial, commercial, and reputational harm that may flow from the mismanagement of material risks.

At the same time, directors are required to consider climate and nature-related risks by corporate sustainability regulations around the world, for example, corporate sustainability disclosure (e.g. the EU CSRD) and human rights and environmental due diligence (e.g. the EU CSDDD) requirements. Liability risk from non-compliance includes regulatory enforcement, fines, reputational damage, and more. But, despite significant overlap, regulatory compliance and corporate risk management are not the same thing. This means that:

Even if sustainability regulations change or are delayed, directors’ duties to manage foreseeable and financially material climate and nature-related risks remain

Furthermore, climate and nature risk management is not – and should not be – merely a compliance or liability-limitation exercise for directors. Instead, it is necessary to secure long-term business resilience and success. This cuts to the core of directors’ legal duties, as well as their strategic, operational, oversight and governance roles.

Alongside managing risks, directors should seek out climate and nature-related business opportunities.

In these circumstances, the main takeaway from the workshop was that directors’ duties require directors to actively manage climate and nature-related risks, but also permit directors to go further, while minimising regulatory scrutiny, by positioning climate and nature as central to business strategy, operations, and opportunity.

Understanding the Core Duties: Loyalty and Care in a Changing Climate

The session unpacked two core director duties – the duties of loyalty and care – and what they mean in the context of climate change and nature loss.

Duties of loyalty and care apply broadly across jurisdictions. While the examples below are based on UK law, Sarah emphasised that similar principles underpin directors’ duties globally across various legal and regulatory frameworks.

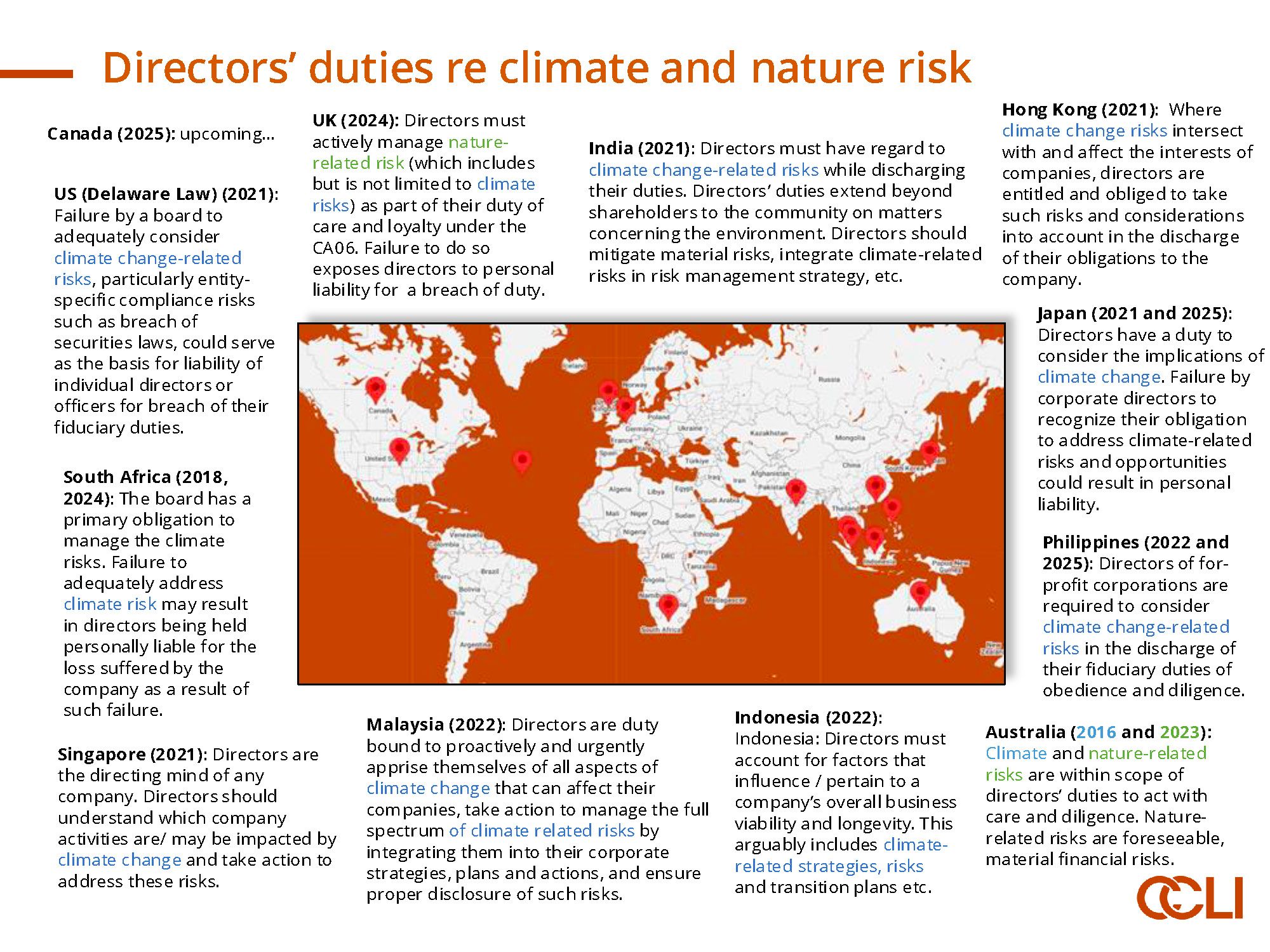

For country-specific insights, see the CCLI and CGI Directors’ Duties Navigator (2024) and legal opinions on directors’ duties in 11 jurisdictions including Japan (2025), England and Wales (2024), Australia (2023) and more.

Duty of Loyalty: Under section 172 of the UK Companies Act 2006, directors must act in good faith to promote the success of the company. Although there is no legal definition of “success” in this context, it has typically been interpreted in financial terms – i.e. the primary purpose of a company is to maximise shareholder value. But the law in the UK – and some other jurisdictions – expressly requires directors to have regard to factors including:

• the long-term consequences of decisions;

• the impact of the company on the community and the environment; and

• maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct.

Such factors capture the principle of 'enlightened shareholder value’, which encourages directors to consider the long-term interests of all stakeholders – i.e. the environment and community as well as shareholders – when making decisions, rather than pursuing short-term profit at all costs. This requires directors to continually consider and balance short-term and long-term interests and risks.

The duty of loyalty is assessed subjectively – i.e. did the individual director genuinely believe, in good faith, that they were acting in the best interest of the company? – unless the director unreasonably overlooks a material factor or risk, at which point they will be held to an objective standard and may face legal liability.

Duty of Care: Under Section 174 of the UK Companies Act 2006, directors must exercise reasonable skill, care, and diligence. This duty is assessed both objectively (based on levels of general competence) and subjectively (based on a director’s particular expertise and role). The focus is on following a sound decision-making process rather than guaranteeing the ‘right’ outcome. To comply with their duty of care, directors must stay informed of and appropriately delegate while maintaining oversight of company affairs. Failing to do so exposes directors to potential liability.

Business Judgment: A notable point raised was the business judgment rule, which affords directors broad discretion to make business decisions and protects directors who act in good faith and with due care—even if their decisions later turn out to have an undesirable commercial, financial or reputational outcome. This means directors are unlikely to face liability for simply making bad decisions, unless there is clear evidence of bad faith, misconduct, or a breach of directors’ duties. For example, completely ignoring material climate or nature-related risks can pierce this protection.

The Evolving Legal Landscape: Sarah highlighted that directors' duties are not static—they evolve alongside shifts in regulation and ‘black letter’ law, soft law standards (like OECD Guidelines), investor and societal expectations, scientific and environmental developments (including changing climate and declining nature), and technology.

What was a reasonable decision in the past may no longer meet today’s standards, emphasising the importance of directors staying updated

Directors’ duties in relation to climate change and nature loss

So, what do these duties mean in the context of climate change and nature loss? Legal opinions on these topics in the UK, Japan, Australia and more have supported the following trends:

So, what do these duties mean in the context of climate change and nature loss? Legal opinions on these topics in the UK, Japan, Australia and more have supported the following trends:

- First, climate change and nature loss are foreseeable and material financial risks to businesses and the economy.

- Second, climate and nature-related risks are not a new category of risk. They must be managed alongside all other types of business risk. (This runs contrary to the mainstream ‘ESG’ narrative that positions sustainability as a separate category of risk that must be siloed).

- Third, and as a result, directors are legally required to manage climate and nature-related risks in the same way as all other business risks.

- Fourth, failing to do so exposes directors to significant liability risk, including personal liability for breach of duty (although this is a high bar), regulatory enforcement (e.g. fines, sanctions, disqualification from office), and other forms of civil or criminal liability depending on the circumstances. This is additional to the more tangible risks of reputational damage, not being re-elected by shareholders, triggering bad leaver provisions, and, of course, the financial and commercial consequences of mismanaging material risks.

What must directors do? Practical Steps for Boards

Boards can actively manage climate and nature risks by:

- Identifying climate and nature-related risks and opportunities arising from the company’s impacts and dependencies on nature, potentially seeking expert advice if necessary.

- Assessing materiality of those risks, ideally using double materiality frameworks.

- Managing and mitigating these risks, guided by structured strategies such as setting science-based targets, consulting business partners and stakeholders, or investing in nature-positive solutions. How directors manage risks falls within their business judgment and depends on the context.

- Disclosing risks and responses transparently according to regulations (if in scope) or voluntary frameworks. This is an opportunity for directors to inform shareholders and stakeholders how they are managing climate and nature-related risks internally and may help mitigate allegations of mismanagement.

- Documenting all decision-making processes to protect against liability risks. Keeping a record of board meetings and discussions around key decisions, particularly the reasons why decisions were taken, may protect directors against claims of mismanagement or breach of duty in relation to climate and nature risks.

Building the Value Narrative

Building the Value Narrative

These five steps set out the minimum standard: what directors’ duties require directors to do. Importantly, these duties are not linked to regulation. They are owed to the business. So, even if sustainability regulations fall away, directors must still work through these five steps to mitigate material climate and nature-related financial risks to the business.

But for companies to future-proof themselves, directors need to go further by investing in long-term resilience measures and innovation. Nature and climate must not be treated as externalities or mere compliance considerations, but rather integrated into core business strategy and planning.

Directors must understand nature and climate as strategic imperatives tied directly to:

- Attracting new investors who increasingly seek resilient, future-prepared companies

- Supply chain resilience against physical shocks (e.g., drought, floods, wildfire risks)

- Access to new markets through green innovation and first-mover advantages

- Reputational benefits that attract customers, partners, and talent

- Operational efficiency through better resource use (e.g., energy, water, land)

- Innovation — tackling nature loss and climate risks can drive entirely new business models and revenue streams

The economic case for investment in climate and nature is clear. The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that restoring ecosystems could generate $7 to $30 in economic benefits for every $1 invested. Moreover, systemic shifts to a nature-positive economy could create $10.1 trillion annually in new business value and 395 million new jobs by 2030 (WEF, The Future of Nature and Business).

Meanwhile empirical studies reviewed by Clark, Feiner, and Viehs found that:

- 90% of studies show that good sustainability standards lower companies’ cost of capital

- 80% show positive stock price performance linked to strong ESG practices

- 88% show better operational performance.

On an individual company level, it’s for directors to understand what climate and nature-related risks and opportunities face the business, and to build the value narrative around that. This can – and should – happen irrespective of what regulations require.

In fact, a recent report by PWC found that, despite political backlash and regulatory uncertainty around ESG laws, businesses remain committed to sustainability as a source of business value. It found that:

- 84% of companies are maintaining or strengthening their climate ambition

- 83% of companies report research and development investment in low-carbon products and services.

- ‘Sustainable’ products can achieve a revenue increase of 6-25% over products without such emphasis.

So even if companies are talking less about their climate pledges and credentials, those that appreciate climate and nature as business opportunities and drivers of corporate value are continuing to act and are doing so beyond the political spotlight.

Top Takeaways

If directors remember just two things:

- Place Duty First: If climate, nature, and broader sustainability risks are foreseeable and financially material to the company (which they are in most cases), directors are legally required to actively manage them — no matter how politicised or delayed regulation becomes.

- Build the Value Narrative: Directors have wide discretion on how to respond to climate and nature-related risks and opportunities. Directors can transform sustainability from a defensive “cost and compliance” issue into a source of business value, resilience, and competitive advantage.

Moving forward, the term “ESG” may fade, but the underlying financial, operational, and governance imperatives to invest in climate and nature-related opportunities will only grow.

The future belongs to companies — and boards — that can integrate sustainability into their business DNA with commercial acumen and strategic foresight

Chapter Zero France and ChangeNOW partnered to co-host a series of events tailored specifically for Non-Executive Board Directors at the KPMG offices in Paris, alongside the ChangeNOW 2025 conference at the Grand Palais.

In part two, we will cover the EU Omnibus and why it could do more harm than good with insights from Nathalie Dogniez, chair of Eurosif, the leading pan‑European association promoting Sustainable Finance.