Co-produced by Client Earth and the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC), this guide offers a practical framework for financial institutions and professionals in Asia to navigate the growing legal, reputational, and market risks associated with greenwashing. Focusing on five common forms of greenwashing, the guide offers real-world examples as well as strategic questions that institutes can use to strengthen the credibility of their climate-related statements and actions. The full guide can be found here.

Key Takeaways for Board Directors:

- Screen your green. Greenwashing is a growing legal and regulatory risk. Although regulatory action remains in its early stages in Asia, there is an increasing volume of enforcement action to target misleading information. South Korea has launched investigations and proposed penalties, and Hong Kong’s financial regulator has stressed the need for oversight. Legal challenges, mostly led by NGOs, whistle-blowers, and competitors, are expanding globally. Asia is starting to see growing pressure from civil society and regulatory agencies, with the Asian Development Bank acknowledging climate-related litigation as a present issue in the region. Therefore, it is important for board directors to interrogate the credibility of green claims made by the company, avoid vague or misleading labels, and ensure they’re supported by clear data and measurable impacts.

- Walk your green talk. Rules and frameworks are being developed to standardise ESG performance for more consistent and comparable assessments. This improves the reliability of third-party ratings, certifications and taxonomies that investors use to assess companies’ and products’ green credentials. Eg. India’s securities regulator has approved new ESG rating rules to aid investors in comparing companies’ green credentials more effectively and Indonesia released a taxonomy to support businesses in describing their green activities. As these clearer, standardised frameworks take shape, stakeholders and investors can measure corporate portfolios and green initiatives more accurately. Boards must ensure internal governance and oversight structures are aligned with public environmental commitments, and that green policies are implemented consistently across departments to stand out in a standardised setting.

- Observe the changing shades of green. Regulatory and supervisory bodies are cracking down on greenwashing. Although climate-related reporting remains voluntary in many Asian jurisdictions, mandatory disclosure standards – such as the EU’s SFDR and CSRD – are being introduced, with others likely to follow. Regulators across Asia are clarifying expectations for the management and disclosure of climate risks in ESG investments of financial institutions. Eg. China’s central bank has issued mandatory environmental disclosure guidelines for financial institutions, and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment now requires certain high-emitting or non-compliant listed companies to report environmental and carbon emissions data. Product and fund labelling regulation has also increased, aimed at reducing greenwashing and helping consumers compare financial product. Eg. proposed ESG labelling rules by ESMA (EU), term usage restrictions by the UK FCA, and disclosure and reporting guidelines for ESG funds enforced by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Board directors must stay informed of evolving regulatory expectations across jurisdictions to ensure compliance and maintain competitive credibility.

What is greenwashing?

Greenwashing – particularly in the finance industry – refers to false, misleading, or deceptive statements or representations about the environmental or climate benefits of a financial product, investment strategy, or a company’s operations. It typically involves suggesting a net positive or neutral environmental impact where business models, products, or activities may cause environmental harm. Importantly, greenwashing does not require intent – regulators and courts may find greenwashing even in the absence of deliberate deception, focusing instead on how claims are perceived in context. Although the term is sometimes loosely applied to misleading social or governance-related claims, its core application remains within the realm of environmental misrepresentation. This guide restricts its focus to greenwashing strictly in relation to environmental matters.

About the organisations

ClientEarth is a global non-profit that uses legal tools to tackle climate change, protect nature, and fight pollution. In Asia, it supports the net-zero transition through legal analysis and capacity building with private, public, and civil society stakeholders.

AIGCC (Asia Investor Group on Climate Change) is a regional initiative that mobilises asset owners and managers across 11 Asian markets to address climate risks and invest in low-carbon opportunities. Representing over USD 31 trillion in AUM, AIGCC promotes sustainable investment, corporate engagement, and policy advocacy from an Asian investor perspective.

The two organisations joined forces, combining focused legal and industry expertise to guide financial institutions and investors in advancing sustainable finance practices and strengthening Asia’s emerging climate finance landscape.

Why greenwashing matters

Greenwashing occurs across sectors but is particularly problematic in the financial industry. Misleading environmental claims have been identified in retail, utilities, automotive, aviation, and fossil fuel sectors. Studies estimate that up to 40% of global green claims may be deceptive. Within the financial sector, greenwashing poses a significant risk, as it misallocates capital, undermines progress toward net zero, creates unfair competition, and erodes investor confidence in genuinely sustainable products.

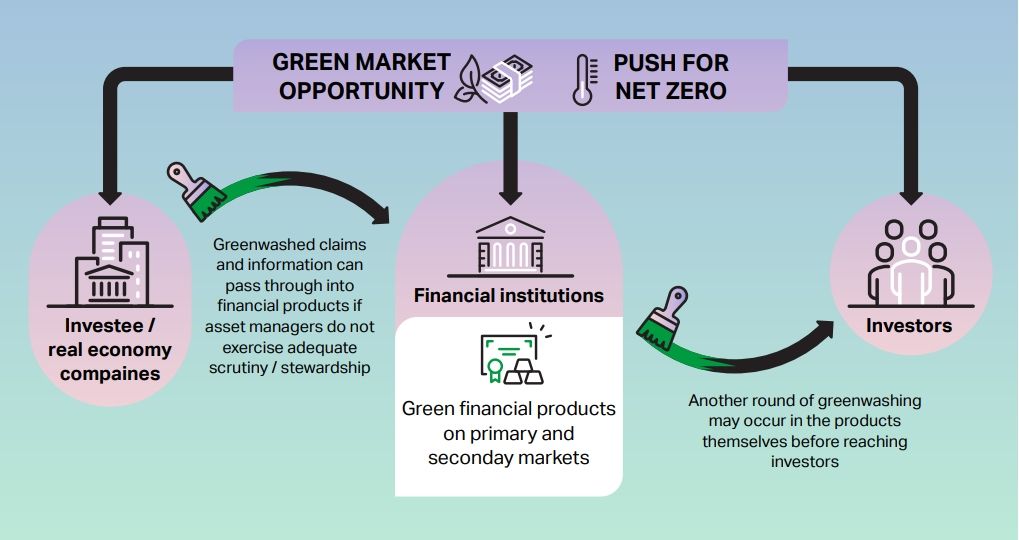

Several factors contribute to the rise of greenwashing in finance. First is the scale of opportunity: green finance in Asia alone is projected to reach US$5 trillion by 2030. Financial products across asset classes – such as green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and ESG-labelled funds – are rapidly emerging to meet consumer and investor demand for environmentally responsible investing.

Secondly, many financial institutions have publicly committed to net-zero targets and joined alliances (eg. Net Zero Asset Managers initiative and the Net Zero Banking Alliance). However, delivering on these commitments is complex, especially without clear standards for implementation and verification. This ambiguity creates space for greenwashing, as institutions may make ambitious claims without the expertise, capacity, foresight and long-term planning needed to support them. Net-zero alliances themselves are now facing scrutiny to ensure members’ commitments are credible and not being used as a marketing shield.

Figure 1. Taken from “Green washing and how to avoid it: An introductory guide for Asia’s finance industry”, showing the investment chain, and two stages of greenwashing (1) claims and information formed by the investee companies, (2) claims that arise from financial institutions.

While enforcement in Asia remains in its early stages, jurisdictions such as the US Securities and Exchange Commission and Australian Securities and Investments Commission have demonstrated their strong commitment to tackling greenwashing from issuing fines to initiating litigation, with regulators increasingly collaborating across borders. Momentum is now building in Asia as well, for example, the South Korean Ministry of Environment launched greenwashing investigations into domestic oil and steel companies SK Energy, SK Lubricants and POSCO, following greenwashing allegations by a civil society organisation. The ministry has also issued a draft law that would introduce fines for companies that misrepresent their environmental impact. Against this backdrop, directors in Asia must be increasingly vigilant to the legal and reputational risks arising from the misuse or misinterpretation of green terminology. Regulatory scrutiny is intensifying across the region, as reflected by Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission’s Agenda for Green and Sustainable Finance, which emphasises that green finance must be properly regulated to safeguard market integrity and investor protection.

Relevance for Directors

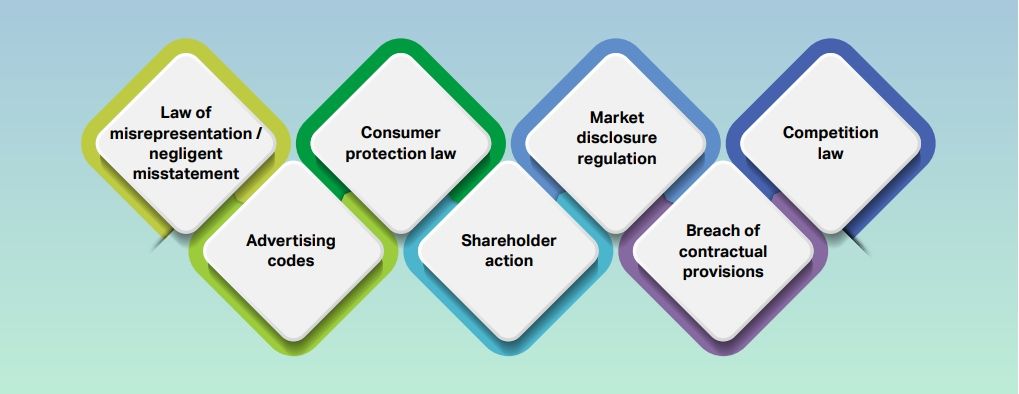

Although greenwashing has only recently emerged as a distinct regulatory focus, and remains governed by existing legal frameworks rather than bespoke climate laws, there is a strong legal foundation for claims against companies within each jurisdiction as outlined below:

Figure 2. Taken from “Green washing and how to avoid it: An introductory guide for Asia’s finance industry”, illustrating legal foundations which greenwashing claims can build on.

Many of these legal avenues already have real-world precedents. Increasingly, legal risk is extending to fiduciaries, falling on the shoulders of trustees and directors. Boards may face legal action or liability for failing to properly manage or disclose climate risks, particularly where this is inconsistent with the organisation’s publicly stated climate commitments. A notable example is the recent case brought against Shell’s board of directors in the UK, alleging inadequate management of climate-related risks in breach of their duties under the UK Companies Act.

Guidelines for preventing greenwashing

As greenwashing disrupts green transitions through distorting capital allocation and eroding trust in sustainability claims, regulatory standards have emerged across five key areas: (1) climate disclosures and accounting, (2) labelling standards, (3) standards on green rating and criteria, (4) green taxonomies, and (5) net zero integrity standards.

The guide identifies four types of greenwashing that have induced legal action: (a) brand greenwashing – which relates to overall greenwashing of an organisation’s profile, activities and ambitions, (b) fund/product greenwashing – which applies to mislabelling or mis-selling products, (c) greenwashed financing – where green financing is granted to assets that are greenwashed, and (d) financial reporting greenwashing – where financial institutions make environmental disclosure-related statements that may be false or misleading. Additionally, a new wave of green-washing including “transition-washing”, greenwashing via offsets, and greenwashing claims filed by competitors – further muddy the waters of the green transition and climate action landscape.

To prevent greenwashing, the Climate Earth and AIGCC propose five key actions:

- Scrutinise the accuracy or credibility of any green claims:

- Ensure that green claims made by the companies are objective, specific, and fully substantiated. Avoid vague or misleading statements and clarify the environmental impact of products or investments. Scrutinise third-party claims and ensure consistency across communications, disclaimers, and disclosure. Use the UN Net Zero Report’s leading recommendations for net zero commitment. For net zero alliances, board directors must understand the commitments their companies have made in joining the alliance, the action required to meet them, and any related disclosure obligations.

- Ensure transparency regarding green objectives is integrated within product and/or financial objectives:

- Clearly articulate investment strategies e.g. negative screens or impact approach, perform due diligence, set clear expectations regarding your organisation’s transition expectations, ensure sustainable finance products follow credible international guidelines when labelled eg. International Capital Markets Association. Disclose any influence over benchmark index of product performance, identify data limitations and outline the consequences of the limitations on the product.

- Align internal practices with the company or fund’s public green image:

- Stewardship activities should be proactive and aligned with the green statements, product labels, or net zero commitments, with transparent reporting of stewardship and proxy voting. Any advocacy and lobbying efforts must be consistent with these green claims. Green policies should be clearly documented and communicated across the organisation, with board-level oversight to ensure compliance. Companies should seek independent, third-party verification of their climate reporting and adequate training should be provided to employees to meet green objectives and reporting obligations.

- Track evolving standards within relevant jurisdictions:

- Directors should monitor evolving reporting obligations, e.g. compulsory sustainability or climate disclosures, the requisite data needed to comply, restrictions on the use of green terminology, and requirements to certify bond issuances as “green” or financing as “transition finance”. Additionally, directors should understand and track stakeholder expectations on sustainability, ensuring these are reflected in green products, financing activities and overall investment strategy. Regarding sustainable communications and marketing, directors should follow international standards linked to climate science rather than local market practice.

- Understand legal duties to investors and stakeholders:

- Directors and fiduciaries acting in the best interest of the company must manage climate risk in their funds / companies / finance portfolios and make appropriate disclosures. While specific duties vary by laws of the jurisdiction, they generally involve regular monitoring and reporting climate risks to the board, and internal audits of risk assessment. Compliance with green investment strategies, financing policies, and other green commitments, should be aligned with relevant science-based decarbonisation pathways. This often requires dedicated internal expertise or external support, with oversight by the senior leadership level or the board. Linking executive KPIs to green outcomes can align incentives with performance on green metrics.

While not prescriptive or jurisdiction-specific, the report presents adaptable, principles-based guidance to promote integrity, transparency, and trust in sustainable finance. It also underscores the need for financial actors to support credible transition efforts across the real economy, in line with fiduciary duties and growing stakeholder expectations. Ultimately it supports Asian financial institutions and regulators in recognising and mitigating greenwashing risks within their own organisations and companies they invest in, ensuring integrity and accountability in the region’s sustainable finance ecosystem. The full guide can be found here.