This guide, produced by the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI) and the Climate Governance Initiative, highlights the material financial risks and opportunities, and directors’ duties of loyalty and care, related to biodiversity loss. It also provides key questions board directors should ask in the boardroom to engage with management and ensure they are meeting their duties to the company.

Biodiversity - why should directors care?

Biodiversity - the variability among living organisms - is being lost at a rate 100 to 1,000 times higher than that of the past million years. This poses significant risk to economic activities and financial assets, which depend on biodiversity. It may also create opportunities for businesses to be part of the transition to a ‘nature-positive’ economy.

It is imperative that boards understand all of the indirect, but very real, implications of biodiversity loss for their business. For example, compromised access to key feedstocks, exposure to chronic or extreme environmental

damage, customer boycotts and moratoria, punitive trade and regulatory constraints, litigation, pressure from investors or premature termination of permits.

Failure to consider biodiversity risks and opportunities in governance and disclosure may constitute a breach of directors’ duties.

Following a short refresher on the relevance of biodiversity and the applicable elements of directors’ duties, the final page includes questions for boards to engage with management.

This update explores:

- The relationship between biodiversity and companies.

- How ecosystem services support many sectors of the economy.

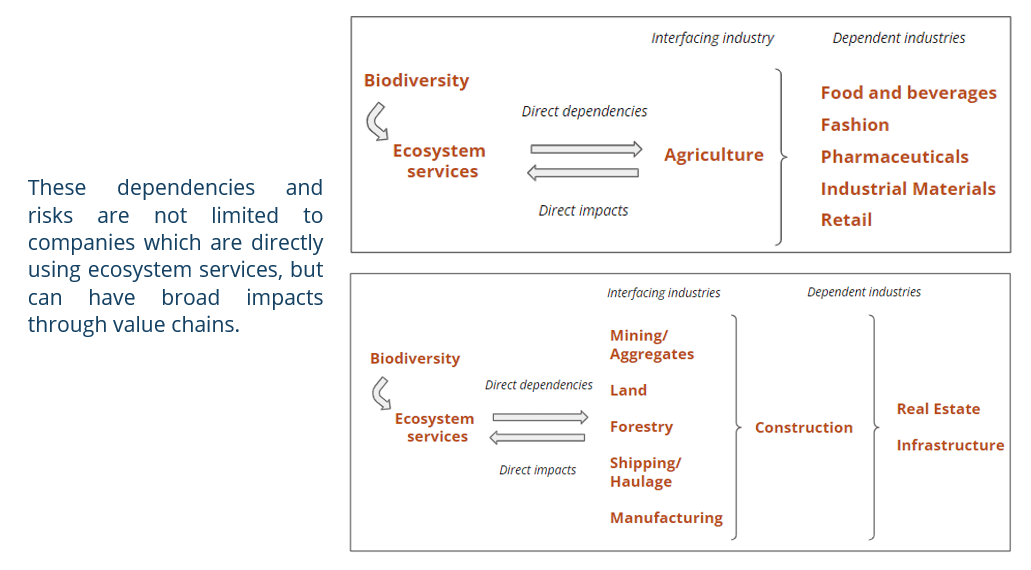

- The indirect nature of many companies’ interface with biodiversity through value chains.

- Changes to the standards of materiality used in assessing biodiversity risks and

opportunities. - Market, social, regulatory and legal context that influences biodiversity risk and

opportunity assessment. - Examples of how directors could breach their duties if they fail to consider biodiversity risks and opportunities appropriately

- Biodiversity litigation risk.

How biodiversity loss affects companies

There is international consensus on the financial and systemic materiality of biodiversity risk, including statements by the Network for Greening the Financial System, the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, governments and national banks.

The functioning of the global economy and the actors within it depend on the services supplied by healthy ecosystems, known as ‘ecosystem services’.

According to the World Economic Forum, US$44 trillion of economic value (over half of global GDP) is moderately or highly dependent on ecosystem services. Biodiversity underpins ecosystem services.

Ecosystem services can be categorised as provisioning, regulaing or cultural services. See below for examples of some sectors that they directly underpin.

Biodiversity and ecosystem services

| Ecosystem service | Relevant sector (non-exhaustive examples) |

|---|---|

| Provisioning ecosystem services provide materials and energy for products. | |

| Water supply | Food and beverages, agriculture, paper, construction and mining |

| Genetic material | Agriculture, forestry and pharmaceuticals |

| Biomass provisioning | Energy |

| Other provisioning services (food, fibre, etc.) | Fashion, retail, fisheries, aviation, automobile, industrials, forestry and pharmaceuticals |

| Regulating ecosystem services regulate and maintain ecosystem processes, supporting industries which rely on the stability of those services | |

| Pollination | Agriculture, fashion, food and beverages |

| Soil and sediment retention | Agriculture, fashion, food and beverages |

| Water flow regulation | Construction and real estate |

| Solid waste remediation, soil quality regulation | Agriculture, construction, real estate, mining |

| Water purification | Food and beverages, agriculture and healthcare |

| Flood mitigation | Construction and real estate |

| Air filtration | Construction, real estate and healthcare |

| Nursery population and habitat maintenance | Fisheries and tourism |

| Local climate regulation | Agriculture, food and beverages, fashion and tourism |

| Biological control | Agriculture, food and beverages, fashion and healthcare |

| Global climate regulation, rainfall pattern regulation and storm mitigation | Agriculture, construction, real estate, oil and gas and insurance |

| Cultural ecosystem services provide non-material benefits, e.g. spiritual, recreation, well-being | |

| Recreation-related or visual amenity services | Tourism and entertainment |

| Education, scientific and research services | Education and science |

| Spiritual, artistic, symbolic and cultural services | Education, cultural, media, tourism |

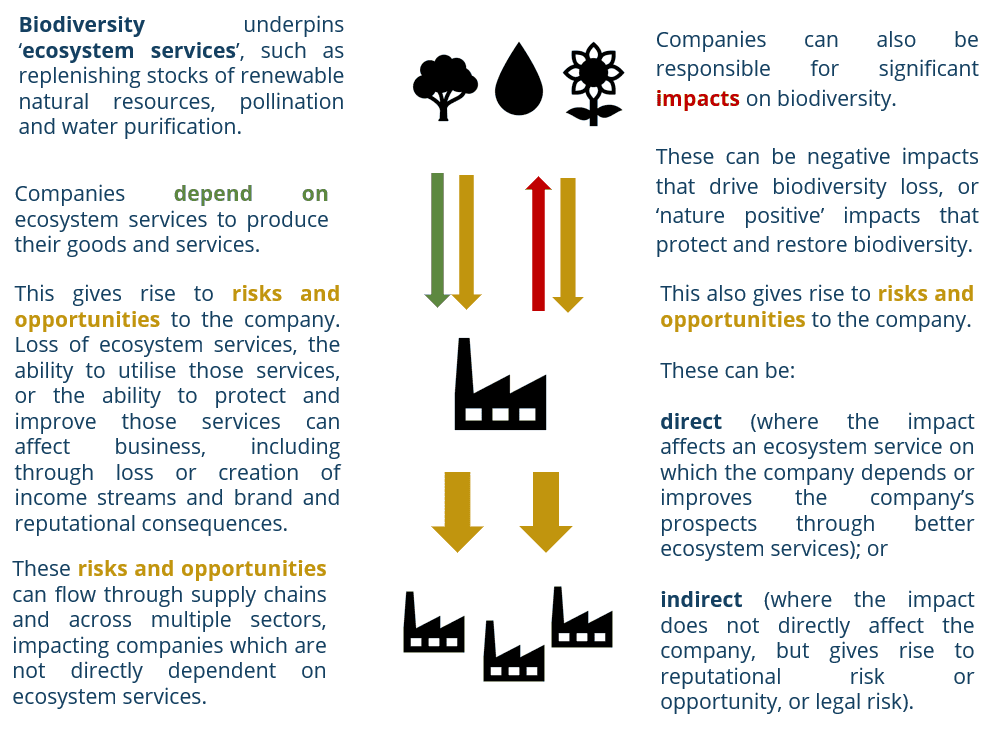

Companies' dependencies and impacts on biodiversity

Many companies have direct or indirect dependencies on biodiversity through their use of ecosystem services or through their value chain. Companies can be responsible for significant impacts on biodiversity, including including by their: use of land and sea space; use of organisms (e.g. for raw materials); contributions to climate change; pollution; and by contributing to the invasion of alien species (the 5 main drivers of biodiversity loss).

Assessment and disclosure of biodiversity risks and opportunities

Companies’ dependencies on biodiversity can create risks to and opportunities for the company, for example where biodiversity loss may affect the supply of goods or income generation.

A company’s impacts on biodiversity can create risks and opportunities, either by affecting ecosystem services on which the company depends or by negatively affecting other parties, creating potential reputational and/or legal risks.

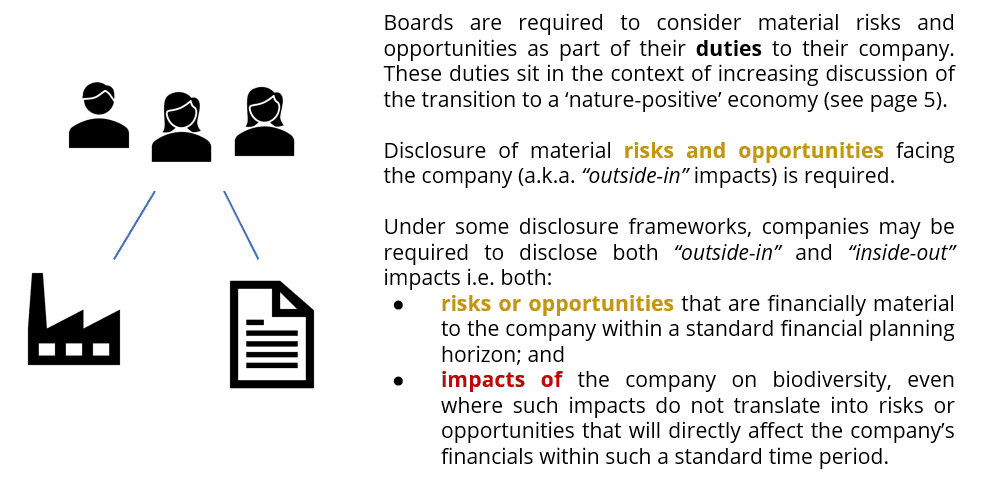

Generally, companies are required to disclose risks to their business that meet the classic definition of financial materiality. However, under emerging and existing disclosure frameworks, this may be changing.

The traditional approach to materiality, known as ‘single materiality’, considers the risks posed to a company (i.e. “outside-in”) within a planning horizon that is considered material to financial valuations.

Some disclosure frameworks adopt a ‘double materiality approach’, as adopted by the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive and the proposed TNFD framework. ‘Double materiality’ requires companies to disclose both risks posed to and impacts caused by the company.

Therefore, companies’ biodiversity impacts that do not create any foreseeable and material risks or opportunities to the company could still fall within directors’ governance and disclosure practices. This is an open question that will require directors to use business judgement.

Directors' duties of loyalty and care

Context

Generally, directors’ duties require acting with care and loyalty toward their companies. Though expressed differently across jurisdictions, these duties are exercised in strategic planning, oversight of foreseeable and material risks, and attesting to the accuracy of disclosure and financial reporting. The law commonly assesses the standard of directors’ care and loyalty by reference to the evolving market, social, regulatory and legal context. The term ‘nature positive’ is gaining traction. Recent developments indicate that discharging directors’ duties may entail consideration of biodiversity:

- Proposed and enacted environmental due diligence legislation around the world is likely to cascade information requests through value chains. This has major implications not just for directly affected companies incorporated or operating in the territories where such legislation is passed but through its cascading effect, for companies outside those territories. It may also influence global best practice. See Quarterly Update 3: Value Chain Due Diligence.

- Courts are considering biodiversity-related cases against companies. See page 7 below.

- The Global Biodiversity Framework (sometimes referred to as the ‘Paris Agreement for Nature’) adopted at the fifteenth conference of the parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in December 2022 (COP15) includes indicative targets relevant to companies, which could, if translated into government policy or legislation, create risks for companies. In Target 15 governments committed to implement measures to ensure that large and transnational businesses and financial institutions assess and disclose their risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity along value chains and portfolios.

- The anticipated frameworks of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) may lead to companies being obliged to make biodiversity risk disclosures in non-financial statements. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has indicated companies should also disclose material emerging environmental risks (e.g. biodiversity risks) in financial statements.

- Existing law requires the disclosure of ‘material’ information (i.e. information which would affect an investor’s decision to invest); therefore, investors’ attention to biodiversity may affect duties of disclosing companies. Investor frameworks indicate a growing appetite by the world’s biggest investors for managing biodiversity risk, which signals that investors deem biodiversity issues to be material. For example, the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge and Nature Action 100. If disclosure of biodiversity risk becomes market practice, it could raise the general standards of care and loyalty not only for directors of disclosing companies but for directors of companies in jurisdictions or sectors where their peers are reporting, by broadening the scope of what is considered ‘reasonable’ for a director in similar positions.

- In addition to biodiversity risk disclosure requirements, investors may request companies to set science-based targets for nature or disclose biodiversity-related lobbying activities.

- Developments in natural assets, impact investing and natural capital accounting are bringing biodiversity into the financial mainstream, recognising its intrinsic value. This indicates a general direction of travel rather than any imminent new requirements for companies.

- Legal recognition of the ‘rights of nature’, in which natural entities are granted legal status similar to a company or person, presents an emerging legal risk with future potential to accelerate biodiversity litigation against companies. This risk is limited to companies operating (including through value chains or subsidiaries) in specific areas where such rights are relevant (areas within over 30 countries defined through local constitutions, statutes or court decisions), who will need to assess whether company activities might breach such rights.

Potential breach

Directors could face the risk of liability for failures to consider biodiversity risks, opportunities and impacts, where this breaches the duties of care and loyalty.

Biodiversity risk does not just include physical risks and opportunities (e.g. in raw materials supply chain) and legal risks (e.g. liability for the company’s impacts) but also includes transition risks posed by policy, regulatory, investor and customer responses to biodiversity loss (e.g. import bans or anti-deforestation laws).

The standard to be met by directors will depend on their company’s jurisdiction and operational context. Biodiversity risks and opportunities may be of higher relevance in jurisdictions with:

- robust frameworks for directors’ duties;

- nature-related disclosure obligations soon to be introduced;

- high awareness of wholesale and retail buyers who may elect to avoid products known to be associated with negative biodiversity impacts;

- significant biodiversity or climate-related litigation; or

- regulators or national banks actively considering biodiversity risks. For example, studies by central banks in the Netherlands, Malaysia, France and Brazil have found their national financial sectors to have high levels of exposure to dependence on biodiversity.

Illustrative examples of developments in Australia, Canada, India, South Africa and the UK can be found in the CCLI report. These type of developments can be found in many jurisdictions globally.

In industries with higher biodiversity risk and opportunity exposure, consideration of biodiversity may already be included within directors’ legal duties. Companies in, or linked by value chain to, the agricultural, construction or food sectors may have higher risk and opportunity exposure.

It is possible that a director may breach their duties by failing to act in good faith or with reasonable prudence in considering biodiversity risks and opportunities, including by failing to:

- consider and govern for foreseeable and material biodiversity risks, for example in strategy and oversight, or in the approval of specific projects or acquisitions, especially where the company operates in a high-risk sector;

- consider in good faith, or by wilfully disregarding, a material biodiversity risk in strategic decision-making where that risk was evident;

- adequately embed biodiversity risk into management processes, or failing to monitor operations, resulting in a failure to keep informed of risks or problems;

critically evaluate or obtain independent review of advice in relation to biodiversity risk; - consider opportunities for the company to adapt in a timely manner to the transition to a ‘nature-positive’ economy, including opportunities to create value from biodiversity or new business models;

- act in accordance with their assessment of risk, if that decision was one which no reasonable director would have made; or

- prevent the company from making misleading disclosures in relation to dependencies, impacts, risks or opportunities.

Litigation risk

There are multiple examples of cases around the world against governments that indicate increasing appetite of litigants for biodiversity claims. This includes the US, Turkey, France, Ecuador, Australia, Argentina, Colombia, China, Costa Rica, Tanzania and the Philippines.

Biodiversity-related litigation is being brought against companies. Claims brought to date generally relate to disclosure obligations, or duties to manage subsidiaries or value chain partners:

- In Australia a potential claim against ANZ Bank may soon be filed on the grounds that the Corporations Act requires its directors’ report to disclose that biodiversity loss represents a material risk.

- In the US, investors have filed a securities class action against wood pellet company Enviva and its directors, including allegations that Enviva misrepresented the environmental sustainability of its wood pellets and its sourcing practices are negatively impacting forest biodiversity.

- A 2021 case against the French supermarket chain Casino alleged that Casino’s yearly due diligence plans failed to detail the environmental and human rights harms caused by the supply of cattle from deforested areas to Casino’s Brazilian subsidiary.

- Cases in the UK, the Netherlands and Canada indicate that courts will not preliminarily strike out claims against parent companies for conduct of foreign subsidiaries. In the UK this includes claims by victims of environmental harms located in Zambia, Nigeria and Brazil. Although substantive judgments in these cases are pending and some of these cases deal with alleged human rights abuses, the same legal principles could allow for lawsuits against parent companies for the impacts of their subsidiaries in biodiversity-rich regions.

While no biodiversity-related cases have yet been filed alleging breaches of directors’ duties, cases filed against directors for mismanagement of climate risk indicate the potential for similar biodiversity claims. For example, a shareholder has brought a derivative action against Shell’s board of directors in the UK over alleged mismanagement of material and foreseeable climate risk.

While market context and evolving best practices suggest that the law permits or requires directors to contemplate biodiversity risks and opportunities in fulfilling their duties, failure may not often lead to liability. In certain jurisdictions, there may not be enough evidence to provide liability; in others, there may be difficulties for potential claimants to meet the bar to establish a claim. However, the increasing number of climate-related cases against companies and directors across the world suggest strong potential for similar cases to emerge in relation to biodiversity loss.

Avoidance of liability is a minimum bar, and directors will want to avoid or mitigate reputational issues by aiming for prudent governance informed by best practice. In order to discharge their duties, directors can ensure that risk management processes assess foreseeable biodiversity dependencies and impacts of the company for materiality and measure those that are material. Directors can then include material dependencies, impacts, risk and opportunities within strategy, disclosure and decision-making.

What should board members ask?

Company directors can use this checklist to help them ensure that they are meeting their duties to the company:

- To what extent are biodiversity risks and impacts embedded into my company’s risk management processes?

- Do I have the appropriate skills and information to assess how biodiversity issues could affect my company and my ability to discharge my governance and disclosure obligations?1

- What training or information would help the board, executive and management teams build our capacity?

- To what extent will this involve external consultants and who will be responsible internally for reviewing and implementing the advice received?

- Can we follow other companies’ practices or join networks to learn from peers?

- Is the management team assessing the company’s foreseeable biodiversity dependencies and impacts?

- Is the management team measuring the company’s material dependencies and impacts on biodiversity and disclosing them in corporate reports? If not, do we have a plan for them to do this?

- Who in my company is responsible for following the development of the TNFD and ISSB guidance and building the company’s capacity to implement them once final?

- Has, or could, my company set science-based targets for nature?

- Does my company have a strategic biodiversity plan, based on identified dependencies and impacts specific to the company?

- Does this plan:

- define the company’s vision, measurable goals, objectives and strategies to address biodiversity risk; and

- ensure that the company’s external activities, including membership of professional associations and voluntary initiatives, align with its goals?