The corporate climate and nature disclosure landscape so far

The evolution of sustainability – and related climate and nature – corporate reporting has accelerated significantly in recent years. Historically, organisations have been required to report primarily on their financial performance, as it has been considered that this information reflects a true and fair view of the organisation’s performance. However, over time, it has become apparent and more widely accepted that climate and nature-related risks are material financial risks that affect value creation for an organisation. Therefore, they should also be managed and reported.

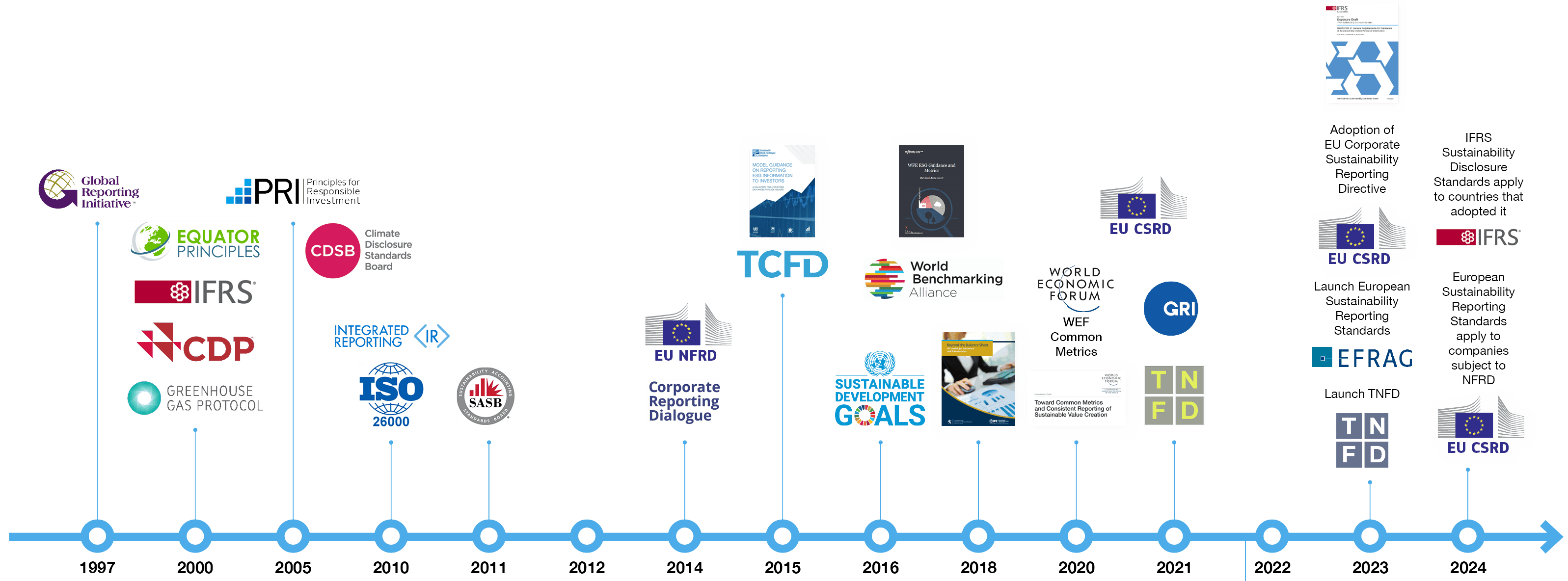

In the 1990s, sustainability reporting at a global level started gaining momentum following the launch of the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative), which provided standardised metrics for environmental, social, and governance (ESG).

Then, the 2000s experienced a wave of disclosure standards consolidation, such as the Integrated Reporting Framework, and the SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) and CDSB (Climate Disclosure Standards Board) standards. Notably, those three standards are now housed by the IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) Foundation, which focuses on providing investors with financial risk information. Moreover, in 2010 the CDP’s questionnaire on climate, water and forests was published and allowed benchmarking of corporate performance on those environmental issues.

As climate change became a more urgent global concern and the world works toward the Paris Agreement, the disclosure landscape saw a growing interest in climate-related risks to business performance. This led to the publication of the TCFD (Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures) Recommendations in 2017.

Lastly, the discourse has now moved to nature, as there is a growing recognition of nature as a material financial risk that is interconnected with climate-related issues. For example, research finds that over half of the global GDP (US $44 trillion) depends on services provided by nature and that nature-related opportunities add up to US $10.1 trillion in annual business value. The TNFD (Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures) Recommendations, published in 2023, are part of the upcoming nature disclosure landscape.

Figure 1. Timeline of frameworks and standards for climate and nature disclosure. Source: extract from 'Understanding the Global Reporting Frameworks', IFC, 2023.

A growing number of organisations are reporting under some type of climate and nature disclosure standard. As of 2024, 14,000 organisations report under the GRI in over 100 countries; in 2023 the IFRS had over 400 signatories committed to adopting its standards; and the same year, companies representing two-thirds of the global market capitalisation disclosed via CDP. Investors are also increasingly considering climate and nature information in their financial decisions. For example, BlackRock, an investor managing over $10.5 trillion in assets, requires its investee companies to report according to globally accepted sustainability disclosure standards and frameworks, such as the IFRS Standards or the TCFD Recommendations (further information on standard and frameworks can be found later in this navigator).

As the climate and nature disclosure landscape is at various stages of evolution, it can be difficult for businesses and boards to understand which are most relevant for their organisation. Harmonisation of key standards and frameworks is happening under the ISSB (International Sustainability Standards Board) – part of the IFRS – which is helping to set a baseline for global sustainability disclosure standards and support a global trend towards corporate disclosure of financially material sustainability issues. Moreover, standards and frameworks with an impact materiality approach are getting traction, such as the GRI and TNFD, and their early adoption will help organisations to be at the forefront of disclosure and be prepared for mandatory reporting.